The shell: the suture

In nautilids, bactritids, and belemnites, the chamber partitions (septa) are mostly hourglass-shaped or simply wavy, while they become increasingly folded the course of phylogenetic history in ammonites. The suture is the line that indicates where the septa joined with the inside of the outer shell. It is only visible if specimens are preserved as steinkerns (internal moulds), which lack the outer shell and represent petrified inner sediment fillings of the former shell. In Paleozoic ammonites, lobesare still simply wavy or angular (goniatitic). In the Mesozoic, however, these lines become increasingly complex and characterized by multiple folds (ceratitic and ammonitic). Previous interpretations that the septal folds increase the stability of the shell and enable the ammonites to proceed deeper into the water column have been proven wrong. Rather, the increasing complexity of the septa produced a significant increase of the inner surface area, which was covered by the absorbent skin (pellicula). As a result, the animal was able to empty the chambers much faster. Compared to Nautilus, ammonites were able to survive the loss of even larger portions of the shell in attacks by other animals (e.g. sharks) by rapidly flooding the chambers (see cephalopods under stress).

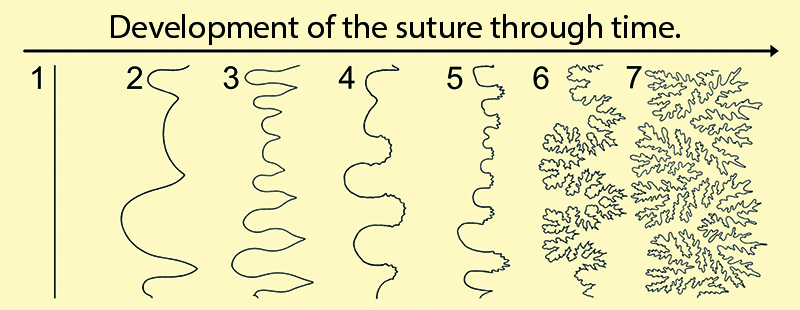

Figure 1:

1 – Orthoceras regulare (nautiloid), 2 – Manticoceras sp. (simple goniatitic), 3 – Schistoceras missouriense (complex goniatitic), 4 – Xenodiscus carbonarius (simple ceratitic), 5 – Otoceras woodwardi (complex ceratitic), 6 – Baculites compressus (simple ammonitic), 7 – Diplomoceras notabile (complex ammonitic). Modified from Peterman et al. (2021). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-87379-5

Figure 2 (In exhibition only)

A – Section through a virtually reconstructed ammonite (Eopachydiscus marcianus), B – Chamber septum of ammonite (A) with strongly curled margin. Modified after PETERMAN et al. (2021)